Carla Lo Coco

San Francisco Bay Area-based writer

Photo credit: Sherry Wong.

Carla Lo Coco is a Bay Area native with an MA in professional writing from Carnegie Mellon University. She’s worked as a communications professional for companies that include Salesforce, Genentech, Schwab, and Wells Fargo. She felt compelled to tell the story of her great-grandfather, so branched out into fiction to write The Trials of Giuseppe Lo Coco while earning a Stanford Novel Writing Certificate. Carla lives in Oakland with her husband and two children.

Carla is seeking representation for her first novel while working on her next project, this time about the unraveling of a childhood friendship.

The Trials of Giuseppe Lo Coco

It’s 1914 San Francisco. Sicilian immigrants Giuseppe and Leonora barely eke out a living after Giuseppe’s health forces them to move from the harsh winters of Detroit. Leonora watches as her husband’s failures mount, pushing him and their family into greater jeopardy.

When Giuseppe loses his job at the notoriously exploitative Gray Brothers Quarry and is unable to collect his back pay, Giuseppe reaches a breaking point. He finds himself standing over George Gray’s body as a pistol drops from his hand. As the trial approaches and unfolds, they each face their fates—Leonora from the home she has managed to hold together for her children thanks to the kindness of strangers, Giuseppe from the jail cell they both believe will be his tomb.

Based on a true story, The Trials of Giuseppe Lo Coco explores the strain on love and loyalty when that promised better-life remains out of reach.

Historical Context

The Gray Brothers

George and Harry Gray operated three quarries across San Francisco starting in the early 1890s at Green and Sansome streets on the eastern side of Telegraph Hill, 30th and Castro, and in Corona Heights. They blew up huge chunks of the rock face in complete disregard for nearby homes and residents. Falling rocks injured adults and children and damaged homes, and the blasts knocked homes off of foundations and broke sewer lines. Despite countless lawsuits and injunctions, the Gray Brothers continued their blasting and quarrying. The city failed to act for decades.

In addition to terrorizing various San Francisco neighborhoods, the Grays used an exploitative payroll system where their workers received increments of pay over weeks and months with a system of vouchers. One disgruntled worker shot and killed the Grays’ payroll clerk in 1909 after various failures to collect his pay. The Labor Department had hundreds of complaints on file, as did the San Francisco District Attorney.

The Crime

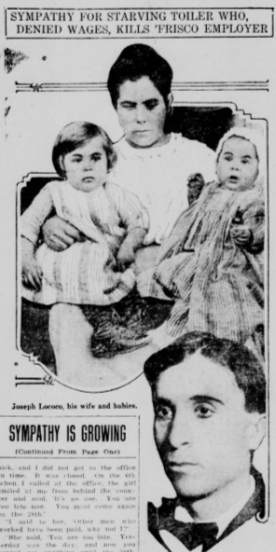

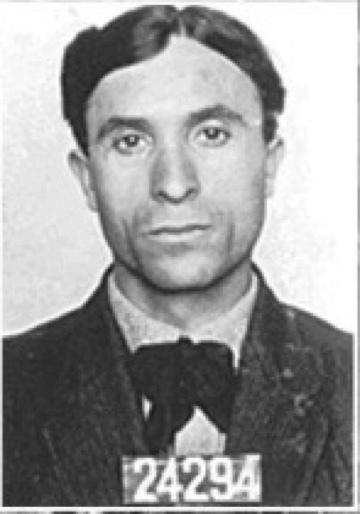

Joseph Lo Coco had worked for George Gray at his Noe Valley Rock quarry, but became too ill to work. They fired him after he missed several days. When he went to collect his wages, the quarry payroll clerks repeatedly told him that he had missed the day to pick up his earnings, and that he would have to return at the next payday to collect his ten days’ pay.

On November 10, 1914, Joseph Lo Coco shot and killed his employer, George Gray. In broad daylight, on a crowded street in San Francisco, in what he later claimed was self-defense, Joseph Lo Coco was launched into notoriety in what San Francisco newspapers called “the trial of the century.”

The afternoon of the murder, a reporter climbed up the hill on Arkansas Street to interview Leonora, Joseph’s wife. She barely spoke any English, but she understood that he was talking about her husband. She enlisted the aid of a neighbor to help in the communication. The abject poverty described by the reporter in his newspaper article prompted an avalanche of aid to the young Lo Coco family. Lawyers volunteered to defend him pro bono.

Public sentiment heavily favored Lo Coco — the trial focused the attention of the entire city on the barren wretchedness of a poor Sicilian immigrant’s home, a victim of a rich man’s greed that left babies starving and a father desperate enough to kill. No one really mourned George Gray — even his family commented to reporters that they “didn’t harbor any unkindly feelings towards Mr. Lo Coco, and only felt concern for those poor little babies.”

On April 17, 1915, two weeks before my grandfather’s third birthday, the jury acquitted Lo Coco by reason of temporary insanity. Deputies could barely control the crowd that rushed forward to congratulate the poor immigrant; the judge threatened to jail the public for being out of order as a cacophony of Italian shouts and cheers erupted at the words, “Not guilty.”